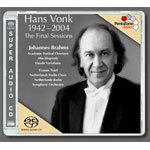

Hans Vonk 1942-2004: The Final Sessions Incls Rhapsody for Alto, Male Chorus and Orchestra

$40.00

Out of Stock

$40.00

Out of Stock6+ weeks add to cart

BRAHMS

Hans Vonk 1942-2004: The Final Sessions Incls Rhapsody for Alto, Male Chorus and Orchestra

Netherlands Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Hans Vonk

[ Pentatone SACD / SACD ]

Release Date: Saturday 22 October 2005

This item is currently out of stock. It may take 6 or more weeks to obtain from when you place your order as this is a specialist product.

"The PentaTone Classics label pride themselves on their first class sound quality... An excellent achievement."

(MusicWeb April 2006)

HybridSACD Playable on all compact disc players

"The PentaTone Classics label pride themselves on their first class sound quality... An excellent achievement."

(MusicWeb April 2006)

The former Music Director of the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra, Hans Vonk, passed away at his home in Amsterdam, Aug, 29, 2004. Maestro Vonk served six seasons as the Orchestra's Music Director, from 1996-2002. He resigned his position in April 2002 due to his declining health.

The distinguished Dutch conductor was much praised during his career for his stylistic authority and mastery of orchestral color. He was known for administering a heightened degree of discipline, clarity, and refinement to any orchestra he worked with, including the SLSO. His interpretations of a score were deeply grounded in an understanding of the composer's intentions. Vonk would sometimes refer to himself as "the composer's friend." Violist Morris Jacob described Vonk's "incredible clarity. It's almost as if he had coffee with these composers. That's what made him so special as a conductor."

"Hans Vonk loved making music with the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra," said Dr. Virginia V. Weldon, Chairman of the SLSO Board of Trustees, upon learning of the Maestro's passing. "This is apparent from the many magnificent performances he and the orchestra gave to St. Louis audiences.

"I had the privilege of seeing a side of Hans that many of our patrons did not see," Dr. Weldon continued, "I hiked in Switzerland with him and his wife, Jessie, two years in a row. Despite his fear of heights, he was a great sport on the hiking trails. He was witty and humorous during the meals we shared with him during these vacations. He enjoyed making jokes and loved to laugh with us. He became a great friend. The music world has lost a great musician; Jessie has lost a dear and devoted husband; and I have lost a good friend."

Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra Concertmaster David Halen spoke of Vonk's musicianship after learning of the conductor's death. "Hans was an illuminator as a musician," Halen observed. "Like a great Renaissance painter uses light to bring the eye toward the essence of his inspiration, Hans clarified textures that brought his musical message to the foreground without any attempt at grandiosity. He lived his life in the service of the music, and in death, because of this devotion, Hans has left the world a far more wonderful place."

Hans Vonk was born in Amsterdam on June 18, 1941, where his father was a violinist with the Concertgebouw Orchestra. His father died when Vonk was three. Throughout his childhood Vonk played and studied piano, yet when he attended the University of Amsterdam he studied law at the behest of his mother. Vonk studied law by day and played jazz at night to support himself.

In an interview with St. Louis magazine, he said he could not find it within himself to become "one of just hundreds of attorneys," and transferred to the Amsterdam Conservatory to study piano. In his second year at conservatory, he played piano for conducting classes. "It was so much, so wonderful," he recalled. "The way the conductor released the music - I went to the director of the school, and I said, 'This is a wonderful thing, this conducting. I would love to study it as well.'"

In retrospect, Vonk's study of law was not such a curious preamble to a conducting career, especially if one considers how the practice of law is based on the rigorous delineation between the factual and the frivolous - a valuable discipline for a conductor concerned with an interpretation that maintains fidelity to a composer's intentions.

Vonk graduated from the Amsterdam Conservatory with honors in 1964. He completed his training as a conductor with Franco Ferrara and Hermann Scherchen. In 1966, Vonk was appointed Conductor of the Dutch National Ballet. A soloist with the ballet company was a striking young ballerina named Jessie, who would become the Maestro's wife.

In 1969, Vonk was named Assistant Conductor of the Concertgebouw Orchestra. In the years to follow he would receive a number of prestigious appointments: Chief Conductor of the Netherlands Opera (1976-85), Associate Conductor of the Royal Philharmonic of London (1976-79) and Chief Conductor of the Dutch Radio Philharmonic Orchestra (1973-79).

In the 1980s, Vonk would become a part of the momentous changes in Europe. As Chief Conductor of Europe's oldest orchestra, the Dresden Staatskapelle, in East Germany, Vonk followed in a distinguished lineage that includes Heinrich Schütz, Richard Wagner, Karl Böhm, Rudolf Kempe and Fritz Busch. Maestro Vonk was the first conductor since Böhm to head simultaneously both the Staatskapelle and the Dresden State Opera.

In 1985, the city of Dresden celebrated the opening of the Semper Opera House with a new production of Der Rosenkavalier, conducted by Maestro Vonk. In 1989, during the Staatskapelle's tour of West Germany, the unexpected fall of the Berlin Wall transformed the tour into a series of goodwill concerts celebrating the reunited Germany.

From 1980-1991, Vonk was Chief Conductor of the Residentie Orchestra of The Hague, then from 1990 until 1996 he was Chief Conductor of the Cologne Radio Symphony Orchestra.

On his first visit to Powell Symphony Hall as Guest Conductor in 1992, Maestro Vonk and the SLSO musicians were taken with each other from the start. Conductor and Orchestra created a memorable interpretation of Bruckner's Sixth Symphony on that occasion. "There was something in the air," the Maestro recalled after he had become Music Director, "a chemistry, a click. From the first moment, I thought, 'This is a perfect match.' When I returned home after my first appearance, I called my agent - and this was well before Leonard (Slatkin) had announced anything - and told her that if there should ever be a position in St. Louis, I would be interested."

The mutual admiration coalesced with the Maestro's appointment as Music Director in 1996. "After 30 years in the profession," Vonk told one interviewer, "it is now time for me to just make beautiful music."

In the United States, taking command of an Orchestra that had grown in recognition and virtuosity after a quarter century under the directorship of American conductor Leonard Slatkin, Vonk immediately began to instill Old World virtues on this New World orchestra. Vonk led the musicians on an in-depth exploration of the core repertoire of classical music. Jan Gippo, who plays piccolo and flute with the SLSO, said "The sound of the orchestra became very balanced, very cohesive. I believe we will play like that for a while. He had an impeccable sense of the pacing of that kind of music."

The Orchestra played beautifully for him, developing a rich, warm tone that was Vonk's signature. Following his first visit with the Orchestra to Carnegie Hall, the New York Times announced, "If Hans Vonk and the Saint Louis Symphony are not celebrating their mutual good fortune, they should start."

On the eve of his fifth season with the SLSO, Vonk told the music critic Heidi Waleson, "Musically, it is the best time of my life." The conductor played to his strengths - Beethoven, Brahms, Bruckner, Schubert, Schumann, Mozart, Haydn. He brought the musicians up to the challenges of Messaien's Turangalila-Symphonie, and audiences too. Taking the French composer's work to Carnegie Hall, reportedly members of the "sophisticated" New York City audience walked out, even as the week before St. Louis patrons met the work with an intense interest.

Vonk had discovered the sound he was looking for with the SLSO. "The musicians have this incredible flexibility," he told Waleson, "and you can mold them to everything. They have the kind of sound I really love. They come very close to an ideal."

When Vonk's sixth season with the Orchestra began in the fall of 2001, it was apparent that the normally energetic man - he hiked the Alps in summer, biked to and from his Central West End home and Powell Symphony Hall - was carrying himself stiffly. As the season continued, the restrictions to his mobility became more alarming to the musicians, the audiences, and to himself. In February 2002, conducting Barber's complex Medea's Meditation and Dance of Vengeance, the Maestro displayed obvious difficulty turning the pages of his score. At last, he could not go on. He was helped from the stage by David Halen, Manuel Ramos, and Vonk's friend, pianist Radu Lupu.

Realizing the serious nature of his condition, Hans Vonk resigned his position of Music Director of the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra in April 2002.

There was still one great performance to come, however. The finale to the season was Mahler's Fourth Symphony. The work demands of musicians vigor, definition, endurance, and clarity over nearly an hour of music. It is a haul, yet with the right conductor and orchestra, it can be like a dazzling epiphany.

Vonk had a special affinity for the symphonies of Mahler. One of the Maestro's and the Orchestra's great triumphs was a performance of the Mahler Third at Carnegie Hall in 1999. Paul Griffiths of the New York Times wrote of that concert, "(Mr. Vonk) conducted a performance of huge dynamic range and sometimes of startling changes in tempo or color, but his choices were dictated less by urgent expressive needs than by a pleasure in the music and a justified pride in how his orchestra can play it." Griffiths concluded his review, "…the last melody sounded, gentle and sure, like the national anthem of heaven."

SLSO Concertmaster David Halen observed that Vonk sought out clarity in Mahler, rather than the sublime. Mahler's symphonies often fall victim to unrestrained musicianship that transforms the works into shapeless - albeit grandiose - spectacles.

Yet Mahler provides as many, if not more, specific notations in his scores than any other Romantic composer. Vonk was attentive to these demands. "If you follow (Mahler's instructions) to the letter," Halen said, "the work comes to life. Hans, then, polices the score, insists these directives happen, which isn't easy."

Hans Vonk led the SLSO over two sold-out concerts of the Mahler Fourth in May 2002. On his last night, especially, he was utterly in command, presenting a cool, and at-times fierce, passion from the podium.

At the close of the evening, meeting the waves of rapturous applause, Vonk was asked to say a few words. The Maestro was known to be loathe to public speaking - one of the criticisms he received as Music Director was his lack of PR skills. He at first refused the microphone, but then quietly told the adoring audience that all he'd had to say over his six years with the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra was in the music.

Which, with his passing, is how it should be.

Tracks:

Academic Festival Overture

Rhapsody for Alto, Male Chorus and Orchestra, Op. 53 (Variations on Chorale St. Antonii)

Variations on a Theme by Haydn